Researchers in York University’s Faculty of Health found that just 30 minutes of visually guided movements per week can slow and even reverse the progress of dementia.

Those in the early stages of dementia who were exposed for 30 minutes a week to a cognitive-motor training game – which used rules to make visually guided movements – were able to slow down the progress of dementia and, for some, even reverse their cognitive function to healthy status.

Previous approaches have used cognitive training alone or aerobic exercise training alone. This study, published in Dementia and Geriatric Disorders, is the first to investigate the impact of combining both types of approaches on cognitive function in elderly people with various degrees of cognitive defects.

“We found cognitive-motor integration training slows down the progress of dementia, and for those just showing symptoms of dementia, this training can actually revert them back to healthy status, stabilizing them functionally,” said lead researcher Lauren Sergio, professor in the School of Kinesiology and Health Science and the Centre for Vision Research at York University.

In the intervention study, a total of 37 elderly people located at senior centres were divided into four groups based on their level of cognition. They completed a 16-week cognitive-motor training program involving playing a video game that required goal-directed hand movements on a computer tablet for 30 minutes a week. Before and after the training program, all participants completed a series of tests to establish their level of cognition and visuomotor skills.

Sergio’s team performed tests to evaluate cognitive function 14 days prior to and following the intervention period, respectively. Her team observed an overall change in all groups and, specifically, a significant improvement in measures of overall cognition in the sub-average cognition group and the mild-to-moderate cognitive deficits group.

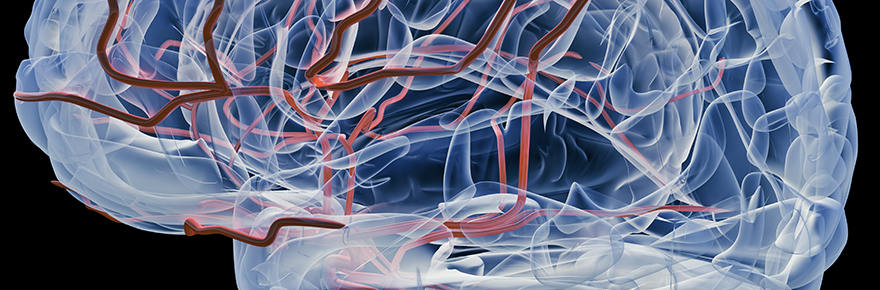

“These results suggest that even in the earliest stages of neurodegeneration, the aging brain has enough neuroplasticity left that if you can train it on this kind of thinking and moving task, it will improve their cognitive skills,” said Sergio. “The brain still possesses the functional capacities to form sufficient new synaptic connections to induce relevant changes on a systems level.”

Sergio adds the findings suggest that repetitive cognitive-motor integration training may in fact strengthen the involved neural networks and improve cognitive and functional abilities. Researchers believe the frontal lobe is “talking” to the motor control areas and this is what is paving the way for success.

The study further found that those in the severe cognitive deficits group who did 30 minutes of this eye-hand task did not decline in their cognitive deficits as expected, but instead stayed the same.

“Generally, you expect someone with severe dementia to have their cognitive function decline over five months, but in our study, they all stabilized,” said Sergio.

The findings show promise, she says, for those who have early-stage dementia because the approach is easy to administer remotely and shows more promise than the basic cognitive training.