Defined as the loss of memory due to brain injury, shock, fatigue, repression or illness, amnesia can be short- or long-term, full or partial. Renowned expert in the cognitive neuroscience of memory, York Research Chair Shayna Rosenbaum, a professor of psychology in the Faculty of Health, has spent her professional life investigating, among other things, the mystery of amnesia.

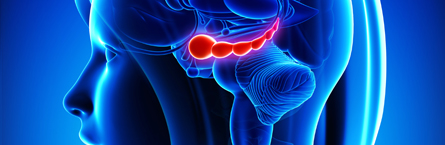

Rosenbaum’s research is unique in that it combines brain imaging techniques with cognitive methods to study learning and memory in patients with memory impairment. Her work looks at different forms of memory, which are critically supported by the hippocampus located within the brain’s medial temporal lobe; the effects of specific brain injuries on learning and memory; and the social and personal effects of amnesia. She is interested in strategies that could be used by amnesic patients to compensate for memory loss and the changes in the way their brains work.

In the following Q&A, Rosenbaum discusses this exciting and highly collaborative research undertaken with the Rotman Research Institute at Baycrest, affiliated with the University of Toronto, and led by Baycrest’s Dr. Jennifer Ryan.

Q. What were the objectives of this research, and what motivated you to decide to look at amnesia this way?

A. To commit information to memory, or to infer information beyond what is directly observed, we need to be able to relate items together in novel ways. This is called relational processing. And it is vulnerable to healthy aging and to a wide range of neurological conditions that affect the hippocampus, including Alzheimer’s disease and stroke. Damage to the hippocampus often results in amnesia. On the other hand, there are other cognitive capacities, such as prior knowledge, or “schemas,” that remain relatively unaffected in healthy aging and in amnesia.

In this research, we wanted to know if we could capitalize on intact schemas – prior knowledge – to support relational processing in older adults and in amnesic patients.

“With our growing aging population, it is crucial that we understand the basis of memory decline and how to remediate areas of impairment.” – Shayna Rosenbaum

This research is timely. With our growing aging population and the many Canadians afflicted by age-related neurological conditions, it is crucial that we understand the basis of memory decline, other capacities that decline together with memory, and how to remediate these areas of impairment.

Q. What was original about this research? How does it add to or build upon existing literature?

A. Prior to our study, there had been a disproportionate focus on memory impairment, rather than on other difficulties exhibited by people with compromised hippocampal function, namely the ability to infer information beyond what is directly observed. This is called transitive inference. It is essential to daily living because it plays a vital role in problem-solving and in guiding behavior in social interactions.

Because memory researchers tend to overlook difficulties in aging and amnesia in the ability to infer relationships among items, no one prior to this research had attempted to alleviate these difficulties by having individuals rely on pre-existing knowledge.

“Our study contributes to [existing] literature by identifying a potential strategy in helping individuals overcome impaired memory and reasoning.” – Shayna Rosenbaum

One of the goals of neuropsychological research is to identify effective strategies that can be used by people to overcome difficulties in memory and cognition. Our study contributes to this literature by identifying a potential strategy, as well as its limits, in helping individuals overcome impaired memory and reasoning.

Q. Please describe how you did the research.

A. In transitivity, participants learn a series of premise relations: A goes with B, not X; B goes with C, not Y. Inference is tested when relational knowledge must be integrated – for example, when given A, C must be selected over Y.

Inference is improved when integration occurs across relations among items that were previously known − for example, yarn goes with scarf, scarf goes with ice skates − even when the relationship between the items was not previously known. For example, when given yarn, ice skates must be selected over a picture frame, presented in a separate set of items.

Q. What were the key findings of this research?

A. The three top findings were:

- We confirmed that transitive inference is impaired in patients with hippocampal damage.

- We found that in healthy aging, prior knowledge helps individuals infer flexible relationships among items.

- When there are more pronounced deficits, as in the case of amnesia due to neurological damage, prior knowledge is not enough to help individuals with memory failure.

Q. What surprised you the most about the findings?

A. Older adults were found to benefit from prior knowledge of items, using this knowledge in a flexible way to infer novel relationships among the items. There are known changes to the hippocampus as we get older, which is why aging has been used as a model to understand hippocampal function.

That’s why we were surprised that a patient with damage to the hippocampal memory system, who was able to identify all of the items − yarn, scarf, skates − and able represent known relations among pairs of items (yarn and scarf, scarf and skates), could not transfer that knowledge across pairs: yarn and skates. This may be because the patient had extensive hippocampal damage or damage to other brain regions that prevented him from applying a strategy that had proven effective in older adults. (See figure.)

Q. Does this work have practical application? How could it be used to help patients?

A. It tells us the limits of strategies that may be beneficial to some memory-impaired populations, but not others. In doing so, it helps guide the development of more effective techniques in future research.

Q. What does this collaboration between York and Baycrest say about the stature of York research capacity?

A. York and Baycrest each offer unique, complementary resources and talent, and combining these strengths in the form of a partnership has led to significant advances in our understanding of how memory works, how it relates to other cognitive capacities and how these abilities break down in aging and following neural compromise.

“Collaborations have helped place York at the forefront of research shaping the way we think about human memory, perception and reasoning abilities.” – Shayna Rosenbaum

Q. How is York viewed as a partner or collaborator on a global stage?

A. The appeal of York as a research partner is seen in our many local and international research collaborations across health and industry sectors, reflected in the successful establishment of the Vision: Science to Applications (VISTA) program.

These collaborations, in turn, have helped place York at the forefront of research shaping the way we think about human memory, perception and reasoning abilities.

What’s next for you as a researcher?

We are currently partnered on several projects relating to the federally funded Vision: Science to Applications (VISTA) initiative, including the use of eye movements to infer memory processes in healthy and memory-impaired populations. One example of this is investigating how spatial information is perceived and remembered in order to navigate efficiently.

This research was funded by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) awarded to Rosenbaum and Ryan to support their program on memory and hippocampal function.

To read the 2016 Hippocampus article, “Semantic knowledge does not support relational inference in developmental amnesia,” co-authored with Shayna Rosenbaum, Jennifer Ryan of the Rotman Research Institute at Baycrest and postdoctoral fellow Maria D’Angelo, visit https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5053239/.

To learn more about Rosenbaum’s work, visit http://www.yorku.ca/shaynar/Dr.R.ShaynaRosenbaum.htm.

By Megan Mueller, manager, research communications, Office of the Vice-President Research & Innovation, York University, muellerm@yorku.ca