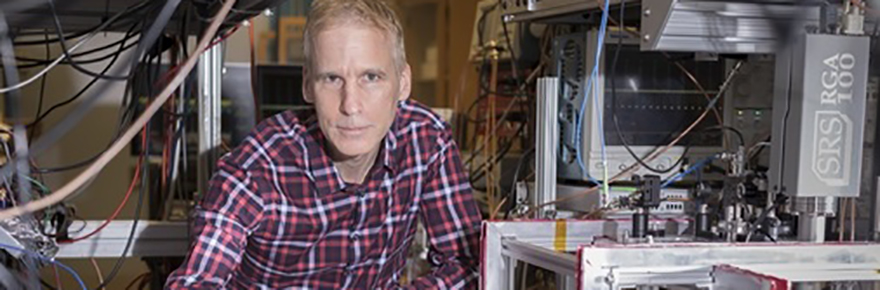

Ramón Alain Miranda Quintana, a postdoc and York Science Fellow at York University’s Faculty of Science, is the John Charles Polanyi Prize winner in chemistry, Ontario’s Ministry of Colleges and Universities announced Tuesday.

He is one of five university researchers in Ontario who have been recognized with a 2019 Polanyi Prize in the fields of chemistry, literature, physics, economic science and physiology/medicine.

“Their work helps advance Ontario’s innovation economy, strengthening our province’s reputation in research, while changing the way we approach and understand issues that directly impact Ontarians,” said Ross Romano, minister of colleges and universities.

The prizes are awarded in honour of Ontario’s Nobel Prize winner John C. Polanyi, who won the 1986 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his research in chemical kinetics.

“Receiving a John Charles Polanyi Prize is a prestigious honour for early-career scientists. York University is proud to see one of our own researchers receive this recognition,” said Rui Wang, dean of science and interim vice-president research and innovation at York University. “Dr. Miranda Quintana came to York University as a York Science Fellow and his work will potentially lead to game-changing advances in areas such as electricity transmission and managing nuclear waste. York University continues to cultivate and support brilliant young researchers like Dr. Miranda Quintana.”

Miranda Quintana is researching new ways to understand the behaviour of complex chemical compounds using computational algorithms, which could lead to new innovations in industry and health. Current tools for theoretical chemistry can explain only about 90 per cent of chemical molecules.

“For the remaining 10 per cent, the existing methods of testing these compounds computationally are so inefficient it could take years to arrive at even the simplest calculation and, in some cases, billions of years,” says Miranda Quintana, who came to York from Cuba in 2018. “That 10 per cent contains molecules that are really important with potentially huge applications.”

These include molecules with rare metal centres that are found in nuclear fuels, nuclear waste and even some enzymes in the human body. Understanding these enzymes better, could lead to medical breakthroughs in treatments.

The goal is to create highly efficient and accurate computational tools that are also safer than traditional chemical lab experiments. “Once we are able to do that, we can apply these new tools to these compounds to understand how they behave, how their function changes when their structure is modified, and how to make them more efficient,” says Miranda Quintana, whose supervisor at York University is the Chemistry Department Chair René Fournier.

Already, Miranda Quintana and a team of colleagues have developed a general and convenient framework called FANCI (Flexible Ansatz for N-body Configuration Interaction) to test various theories about how these complex compounds behave and function using simple calculations, a combination of math and coding.

New tools such as FANCI would potentially allow researchers to understand how to modify these compounds so they convert energy more efficiently at regular temperatures, rather than needing to be cooled to close to minus 273.15 degrees Celsius, as is the case now. This could make the creation of superconductive materials possible and hold the key to revolutionizing the power industry, creating microscopic data storage devices, and better quantum computers. It could also lead to the creation of new nuclear fuels and a simpler way to dispose of nuclear waste.

The idea is to make FANCI software available on open source so researchers can study processes, such as magnetism, superconductivity and thermodynamics, and have a reliable answer much more efficiently than with currents methods. It would speed up the testing of ideas and lead to faster innovations.

The 2018 Polanyi Prize winner for chemistry was also from York University, Assistant Professor Christopher Caputo, whose research explores ways to remove precious metals from the manufacturing process for plastics, pharmaceuticals and other industrial products. His goal is to make production less expensive and more sustainable.

The Polanyi Prizes are awarded each year to innovative researchers in Ontario who are either continuing postdoctoral work or have recently gained a faculty appointment. Each of this year’s winners will receive $20,000 in recognition of their exceptional research in the fields of chemistry, physics, economic science and physiology/medicine.

The major emphases during its first year will be to increase tri-council grant applications and success through a supportive skills and mentoring program for new faculty members at York University. In keeping with that goal, the Research Commons has organized two workshops for January:

The major emphases during its first year will be to increase tri-council grant applications and success through a supportive skills and mentoring program for new faculty members at York University. In keeping with that goal, the Research Commons has organized two workshops for January: