A major new declaration co-initiated by York University professor and philosopher Kristin Andrews affirms there is strong scientific evidence that not just mammals and birds, but potentially all vertebrates and many invertebrates, possess conscious experiences.

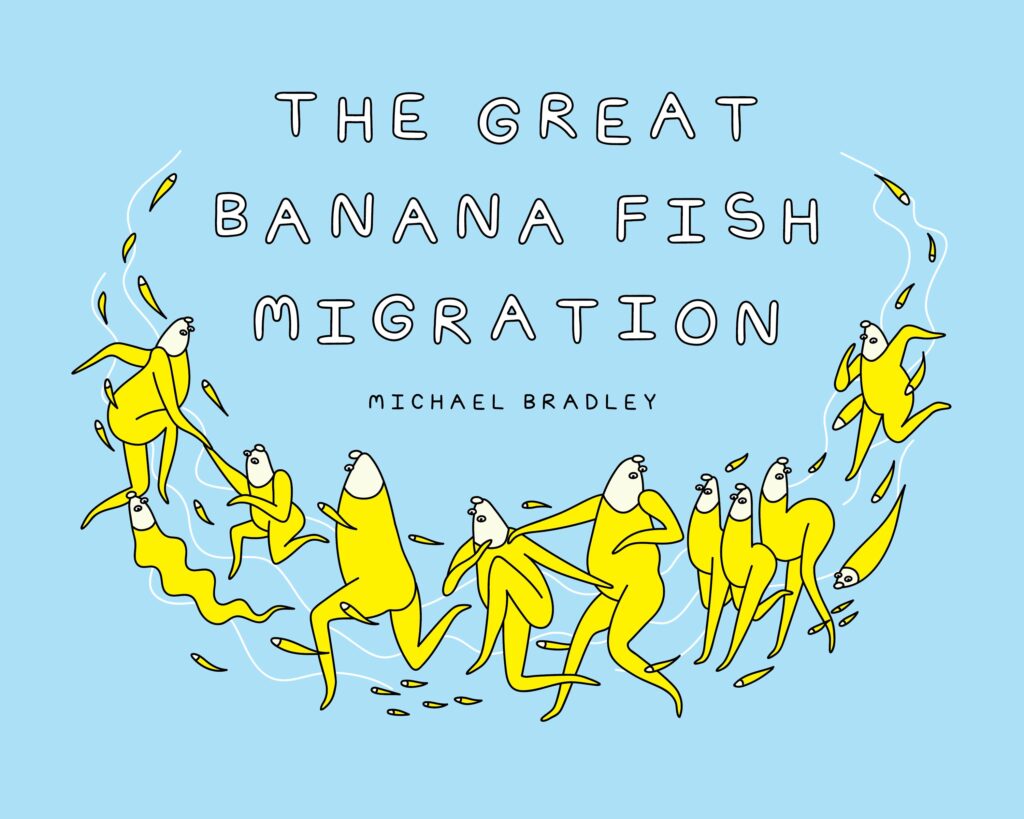

The New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness, unveiled on April 19 at a conference at New York University, states that the empirical evidence indicates “at least a realistic possibility” of conscious awareness in reptiles, amphibians, fish, cephalopod mollusks like octopuses, decapod crustaceans like crabs and lobsters, and even insects. Andrews co-initiated the declaration along with Jeff Sebo from New York University and Jonathan Birch from the London School of Economics.

“Recent research has shown stunning evidence of consciousness-related behaviours in a wide range of animals,” says Andrews, a professor in the Faculty of Liberal Arts & Professional Studies. “The declaration affirms that we can no longer assume these creatures are insentient or incapable of feeling.”

The declaration – which has already been signed by more than 80 leading scientists and philosophers across disciplines – focuses on the most basic form of consciousness – the subjective experience of being an organism and the ability to feel sensations such as pain, pleasure and hunger. While higher-order consciousness involving self-awareness is not attributed, the statement says it would be “irresponsible to ignore” the possibility that these animals can have positive and negative experiences.

For Andrews, the York Research Chair in Animal Minds who has studied animal cognition for more than 30 years, the evidence from recent studies on seemingly conscious behaviours in creatures including bees, crayfish and wrasse fish is compelling.

“We’ve seen bumblebees exhibiting placid, playful behaviours for no apparent reason other than enjoyment,” she says. “Crayfish show anxious behaviours that change when given anti-anxiety medication. Wrasse fish seem to recognize bodily markings when shown a mirror.”

Such findings challenge the assumption that invertebrates and cold-blooded animals are insentient automata. The declaration argues that when there is a realistic chance an animal has conscious experiences, we are ethically obligated to consider its welfare interests.

“It doesn’t mean we can’t ever eat them or use them,” clarifies Andrews. “But it does mean we need to recognize they likely can feel pain and pleasure, and minimize the negative experiences we impose on them.”

While the declaration doesn’t prescribe policies, Andrews hopes it will prompt wider consideration of how human activities impact invertebrates. She points to the need to include cephalopods and crustaceans under animal welfare regulations in Canada, alongside chickens, pigs and fish.

More profoundly, Andrews sees an opportunity for new scientific insights by studying consciousness across a broader range of organisms. “If even simple animals like worms or flies are conscious in some way, they could provide a revelatory model for understanding the fundamental nature of consciousness, without the confounding factors like language that make human consciousness so complex.”

By expanding our “circle of moral consideration,” as Andrews puts it, the declaration opens perspectives on the richness of subjective experiences pervading the natural world. “It offers the possibility of feeling a wider, deeper connection to all the creatures around us.”

Andrews and her colleagues hope The New York Declaration will be an impetus for more research, greater ethical deliberation and, ultimately, a heightened societal valuation of the experiences of non-human minds.