By Elaine Smith

In a desire to commit, in material ways, to York University’s Decolonizing, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (DEDI) Strategy, the Faculty of Graduate Studies (FGS) held several roundtable discussions at its Faculty Council. From these discussions, a motion to infuse a commitment to DEDI into the standing committees of FGS council was passed.

The roundtables revealed lived experience of Black graduate student isolation and a pressing need for mentorship and community building. FGS hosted several conversations with Black graduate faculty, folding in Black graduate students to co-create a plan to address isolation and lack of community. It culminated in a Fall 2023 community gathering.

The Faculty’s work to reduce isolation and build community reflects an earlier FGS commitment to “partner with various programs at York and in the broader community to identify and dismantle the barriers that arise serially and increase over time to disadvantage and dissuade Black students from pursuing graduate studies, especially doctoral studies, in every discipline.”

Mentorship is a valuable way of assisting Black and racialized students in overcoming barriers to pursuing and thriving in graduate scholarship, offering students personal insights and support. Mohamed Sesay and Jude Kong, two Black professors who teach courses and supervise graduate students, shared their thoughts with Innovatus on their own approaches to mentoring racialized students.

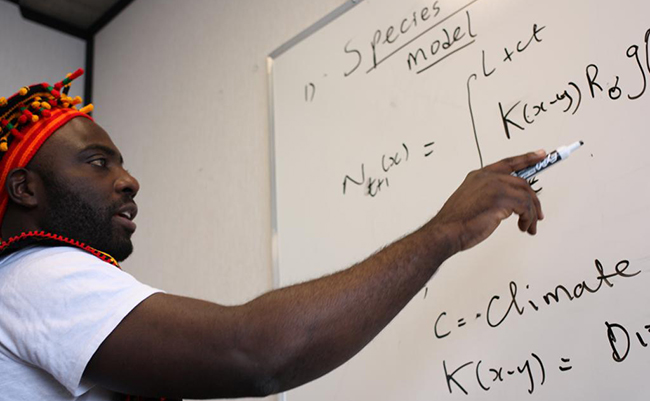

Sesay, an assistant professor of African studies and a native of Sierra Leone, views the barriers as an institutional challenge arising from their history. He realizes that universities were designed for immigrants who arrived here from 18th- or 19th-century Europe, making it clear to him that those from other cultures may find additional challenges in adjusting. He makes a conscious effort to serve as a mentor for graduate students from racialized backgrounds; eight of his 10 current graduate students are racialized.

“Institutions of higher education in western countries weren’t created for people like me,” said Sesay. “As a result, the structures, the rules and expectations, the standards and requirements were not put in place to accommodate graduate students like me or to help us thrive in the same way as non-racialized students.

“In order to do well, there are other issues for us that arise from the structures in place that someone who isn’t racialized may not be able to identify. People may not realize that many racialized students have grown up somewhere else, so they aren’t exposed to the same experiences as those who grew up in Canada. They come with a history that is different and it requires an effort to feel as if they belong to this space.”

Sesay said programs are opening space and incorporating decolonization, equity, diversity and inclusion, but “there is still a long way to go. If there were no issues with equality, we wouldn’t need DEDI.

“It’s not as if we’re compromising our standards,” he continued. “We expect racialized students to meet the same rigorous academic standards and expect them to be critical and creative thinkers, but we can’t be insensitive to other issues they’re dealing with, or they may not be able to fully realize their potential.”

In teaching and supervising racialized graduate students, Sesay takes the need to support them seriously and devotes time to connecting with them.

“I show understanding and empathy and try to share the challenges that I went through myself,” Sesay said. “I’m ready to talk with them and explore what they need to do to overcome challenges. I make myself available and, sometimes, that means talking about issues beyond research that impact academic excellence.

“I’m open to them, not dismissive. Canada is multicultural, but racialized minorities face difficulties trying to make this their home. I want to show them through my experience that it is possible for them to achieve excellence. There’s no straight roadmap or manual, but you can share understanding; you try to support them in navigating this space and boost their confidence.”

Kong, an assistant professor of mathematics and founding director of the Africa-Canada Artificial Intelligence & Data Innovation Consortium, bases his approach to mentoring racialized students on his personal experience growing up poor in rural Cameroon.

Without the emotional support from his family and financial support from the women in his community, he feels he would never have been able to attend secondary school, let alone realize that greater opportunities existed. He tries to recreate this sense of familial support with his graduate students; all four of his postdoctoral Fellows (two of whom are Black) and four of his five graduate students (four of whom are Black) are from racialized backgrounds.

“You don’t know what you don’t know,” said Kong. “You may grow up only being exposed to certain things; if you’re not aware of research, you won’t think about it; it’s not the typical subject of conversation around the dinner table. Most people choose their careers based on the signals picked up by their subconscious memories during their formative years – what is discussed at their dinner table and what they see around them. For Black students whose parents, uncles, guardians and ancestors were not exposed to these opportunities, it’s a different situation. The Black community needs more assistance to understand what the options are.”

In the classroom, as well as in the research context, “I strive to create a sense of family where students are confident in voicing their opinions, just as they would at home. It’s a judgment-free zone where they can admit that they didn’t know something or ask for assistance without the fear of being judged,” said Kong.

Kong also believes that building the students’ confidence is important, since, at a young age, they may have absorbed subconscious messages telling them that they don’t belong or can’t measure up to people from other races when it comes to fields like mathematics. He works to create an environment that is supportive, rather than competitive, because everyone has different talents.

“Keeping them moving forward and allowing them to see that they can handle the work is crucial,” he said. “We’re adding more data points to their experience until they reach that tipping point where they feel comfortable.

“I had nobody I could look up to growing up, but I had a community and allies who helped me go to school and housed me during my college days. My doctoral and postdoctoral supervisor were real advocates, and here at York, people like President Rhonda Lenton and Provost Lisa Philipps have created a structure and space to allow me to succeed. I want to help people like me who have no pathway. I want to show people who have nothing that here is someone from nowhere who has succeeded.”

He added, “York University is about giving opportunities to those who otherwise wouldn’t have it. I call it Canada’s historically Black university.”

York’s Framework on Anti-Black Racism states, “Going forward, we will be responsible and accountable to the diverse constituencies of our community including Black community members, recognizing that bringing about systemic change is everyone’s responsibility.”

Both Sesay and Kong are role models in accepting that responsibility.