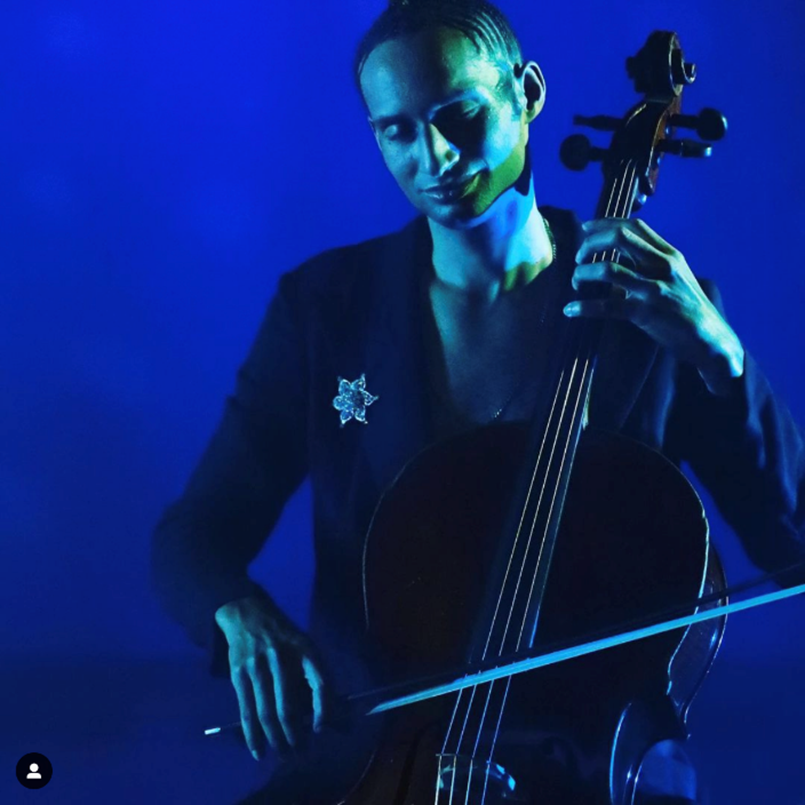

The Faculty of Environmental & Urban Change (EUC) welcomes visiting Artist-in-Residence Zeelie Brown from May 11 to 19.

Brown’s artistry stems from her upbringing in rural Alabama. She creates Black and queer refuges called “soulscapes” – blending sound, performance, installation, wilderness and more to provide solace and challenge systemic oppression.

Hosted by EUC Professor Andil Gosine, Brown will collaborate with the Faculty to create a quilt, exploring the intersections of Black and queer identities and nature, which will be shared at Gosine’s keynote lecture at the Sexuality Studies Association conference as part of the Congress of the Humanities and Social Sciences on May 29.

Staff, students and faculty are encouraged to attend a meet-and-greet with Brown on May 18 at 10:30 a.m. in HNES 138.

Brown met with graduate student researcher Danielle Legault to talk about her upcoming visit.

Q: Can you please share a bit about who Zeelie Brown is?

A: Well, I am an installation artist, cellist and butcher. I am from the woods of Alabama and San Antonio, Texas, where I grew up going back and forth between both places. In my practice I am very much concerned with environment and space. I’m concerned with the ideas of wilderness, Black people’s experience of wilderness, the idea of wilderness as a constructed place, and how queerness, humanity and grace intersect in order to envision and build a more sustainable future.

Q: Can you describe what goals you have for your visit to Toronto and York University?

A: I’m only here for a week, so I’m excited to engage in the exploration of art, craft and culture and to share my perspective, the place I come from and the struggles of that place. These include struggles around adequately weatherproofed housing, the continued colonial legacy of environmental racism, the racism embedded within the landscape architecture of the American project – America being considered a continent and not just a country here – and struggles around place building and the intersections of Blackness, queerness and different identities. And more than all of that, the ability to create from, and beyond, those places.

I’m also excited to learn more about Canada and about Toronto. I’ve met other queer activists through work that I’ve done in the past that I’m interested in following up with. I’m excited to see where our struggles can meet one another and support one another.

Q: You will be working on a project with Professor Andil Gosine while you are here. Can you share some details about that?

A: I’ll be making a collaborative community quilt with York University students and Professor Gosine, centered around ideas contained within his book, Nature’s Wild. The quilt will be a meditation on the intersection of the students’ own personal expressions of their identities and their own interfaces with nature and the ideas of Blackness, wilderness and being from the margin. So, we’re making a quilt, but I’m really interested in pushing the boundaries and exploring what form the quilt will take.

Q: Can you speak about the significance of quilting and how it can push boundaries?

A: In Alabama, we’re world-renowned for our quilting tradition. But to me, quilting is about taking the things that are left over and making art of the discards. It comes from a very long African tradition of abhorring waste. Lots of traditions have this, where “waste not, want not” is traditionally part of the culture.

I think often art is seen as a solitary exercise and not as a means of holding and tying together a community. But what did those quilts in Alabama do? They reminded people of their lost loved ones. They kept people warm. They have a very practical function. And in a situation of enforced dearth, where a Black rural culture that has given everything to the American project is being inhaled, robbed and tied to a racist myth constructed to keep the plantation class rich in their culture and power. The community takes its scraps and makes art and warmth, and joy and love.

Q: Is there anything you would like to share with the York community before your arrival?

A: I want to thank Toronto, York and Professor Gosine for having me here. I would like to emphasize thinking about the folks back home in the Black Belt who, due to the soil tectonics of that region, which were very conducive to growing cotton, have limited, if any, access to adequate sewage and are penalized by the state for the state’s failure. I want to uplift the work of Black folks in rural America.

When we slow down and take time for the rituals, like quilting, cooking, care, cultivating – when we start viewing these acts as important as profit, things start coming together and problems start getting solved. But when everybody’s after a quick buck, there’s often only so many quick bucks to be had.

Going back to what the goal of my time at York is; the goal of my project is to slow down, to create community and to revive traditions that are nearly lost because they don’t make money fast, yet have kept folks alive through some of the most harrowing and wretched treatment that humans have ever inflicted upon each other.