The state-of-the-art telescope is the result of a collaboration between NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency and is the most powerful telescope ever built and there is an expert research connection in the Faculty of Science at York University.

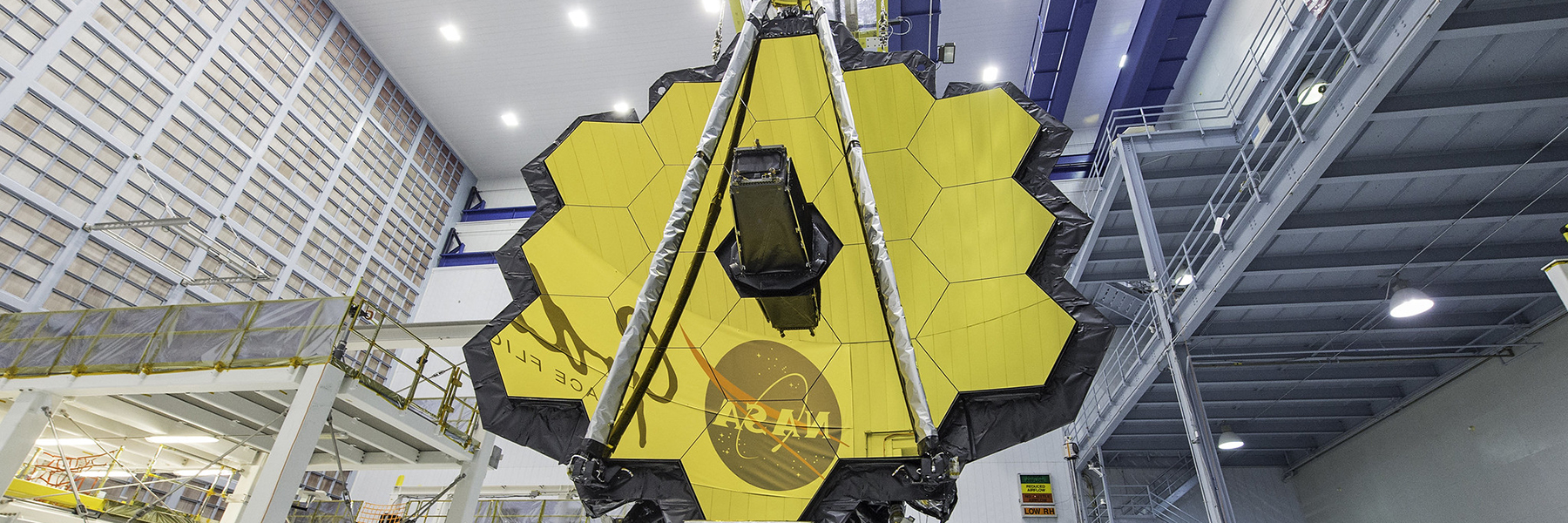

The new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) – a collaboration between NASA, the European Space Agency and the Canadian Space Agency – is expected to launch this month with the Canadian-built Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS). It will take images and spectra of fainter objects than the Hubble Telescope ever could, and it’s creating an astronomical amount of excitement.

What will the telescope do for astronomy? “Everything. It’s the most powerful telescope of all time, blowing away what the Hubble Space telescope can do. It will completely revolutionize all aspects of astronomy,” says York University Associate Professor Adam Muzzin of the Faculty of Science.

One of the things this new telescope will be able to do is see infrared light. This will be important for Muzzin, a member of the Canadian instrument team that built the NIRISS, as he leads one of the working groups on the large Canadian NIRISS Unbiased Cluster Survey (CANUCS) project. The NIRISS instrument can take higher resolution images than Hubble and will allow Muzzin and other astronomers to better study objects in space, including the formation of planets, as well as distant galaxies. It’s a project York grad student Ghassan Sarrouh, a next generation astrophysicist, is currently working on for his MSc thesis.

The CANUCS project will look at how some of the first galaxies, some 13 billion light years away, were formed and how they grew. But as Muzzin says: “The universe is expanding, with everything moving away from us, and so the light coming from distant galaxies is stretching and shifting towards the red part of the electromagnetic spectrum. If we want to see far-away galaxies from the early days of our universe, we need to able to see infrared.”

Muzzin is one of the lucky few to have guaranteed observing time on the telescope for his work on the instrument, along with York Visiting Professor Cemile Marsan in the York Department of Physics and Astronomy, one of only 10 Canadians to receive their own observing time on the telescope in open competition.

Marsan’s project will look at massive, extreme galaxies in the distant Universe that were fully formed when the Universe was less than 10 per cent of its current age. According to physics theories, these galaxies should not exist.

“Over the last decade, astronomers have compiled a myriad of lines of observational evidence hinting that these extreme structures – being 10 times more massive than today’s Milky Way – must exist in the young Universe, but we can’t say much more about them due to current instrumental limitations,” says Marsan. “With JWST, we will be able to ‘see’ for the first time how such rare and exceptionally massive galaxies were able to assemble during an epoch when the Universe is expected to be busy building smaller structures.”

Are these galaxies experiencing a rapid build-up of stars in conjunction with the growth of their supermassive black holes at their centers? Is there something unique about the environment they reside in? These are just two of the questions Marsan hopes the new telescope will help answer.

To learn more, watch a video created by freelance science journalist Dan Falk when he was a Science Communicator in Residence at York University.