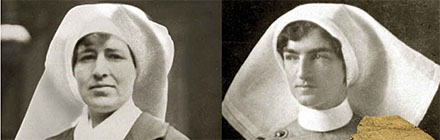

In the First World War, Canada dispatched women to the front as nurses – officers in the Canadian army – a role often overlooked in the annals of history. Editor Andrea McKenzie offers unprecedented insight into the struggles and successes of these women in War-Torn Exchanges: The Lives and Letters of Nursing Sisters Laura Holland and Mildred Forbes. McKenzie is an associate professor in the Writing Department in the Faculty of Liberal Arts & Professional Studies.

Laura Holland and Mildred Forbes were best friends and trained nurses who sailed to England in 1915. They were among the approximately 2,800 Canadian military nurses sent overseas with the Canadian Army Medical Corps, the only group of nurses in the Allied forces to have the rank and pay of officers. Their official title, nursing sister, was equivalent to a first lieutenant. Matrons had the relative rank of captain and the matron-in-chief the rank of major.

Holland and Forbes’s vivid letters home over the following four years reveal their gendered perspective of the war and shed light on the active community of women at home who worked to support nurses and hospitals overseas, including Cairine Wilson, who served as Canada’s first female senator.

“Our nurses are often remembered as ‘angels of mercy’ and idealized in Canadian war memories,” says McKenzie. “Laura’s and Mildred’s letters home show nurses to be much more complex than this simplistic rendering. They coped with harsh living conditions, the trauma of nursing men with severe wounds and illnesses, gender discrimination and the irritations of living under military restrictions throughout the war.”

Holland and Forbes’s journey as independent, socially elite women from Montreal to the extreme stress of war will take readers through the hospitals and casualty clearing stations in France, Belgium and the Mediterranean front, including Gallipoli. They needed to possess physical endurance and emotional stamina; the hours were long, the work was hard and the severity of wounds were traumatic.

“Their friendship was the one stable element for them in an otherwise chaotic war,” says McKenzie. Their letters reveal Forbes’s sense of humour and Holland’s skills as a negotiator and mediator. The letters were “a remarkable discovery – a continuous account of the war told by two friends. Where one voice stopped, the other continued.”

The pair saw it as their responsibility to take care of both the soldiers’ physical condition and emotional state. For soldiers, the hospitals became havens amidst war zones.

“As well as administering treatments and drugs, nurses also supplied comforts to the soldiers, often spending their own funds to supplement hospital diets and to provide treats for their patients,” says McKenzie. “Nurses often lived in tents or huts, living in relatively primitive conditions,” she adds.

They were known for offering a sympathetic ear to the soldiers’ traumatic experiences, often relating those stories in their letters home. There was friction, however, between nurses and doctors when the nurses felt patient needs were not met.

“A popular myth about nurses of the time is that they were passive and subordinate to doctors,” says McKenzie. “The Canadian nurses showed that they were not: they spoke up and made ‘bally nuisances’ of themselves when they thought it was necessary.”

While the nurses at the front fought to keep soldiers alive, nurses at home in Canada fought for the registration of nursing as a profession, an argument aided by the valuable skills demonstrated by nurses like Holland and Forbes.

“Laura and Mildred felt that their professional skills were valued and useful,” says McKenzie. “This and their friendship kept them resilient and strong.”