Every culture has a lesson to teach us if we are willing to listen.

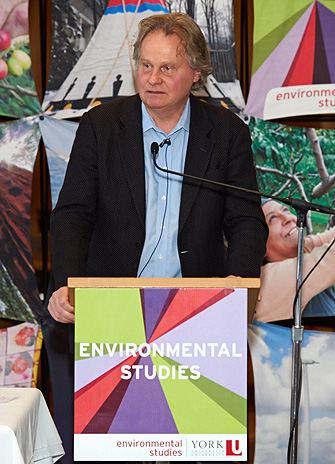

On May 6, Wade Davis (LLD Hons. ’14), professor of anthropology and BC Leadership Chair in Cultures and Ecosystems at Risk at the University of British Columbia, delivered a lecture at York’s Keele campus, titled “The Wayfinders: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters in a Modern World.”

The talk constituted the third installment of the Koerner Lecture Series, established in appreciation of the Koerner family for their substantial contributions to the Faculty of Environmental Studies’ Las Nubes Project supporting research in Neotropical conservation in the Faculty’s Las Nubes rainforest in Costa Rica. More than 130 York University faculty, staff, students and alumni gathered for the lecture.

Faculty of Environmental Studies (FES) Dean Noël Sturgeon kicked off the evening with a warm welcome to Michael and Sonja Koerner. Sturgeon conveyed the Faculty’s appreciation of their support. FES Chair of Neotropical Conservation, Professor Felipe Montoya-Greenheck, then described York University’s Las Nubes project and introduced Davis.

Upon his appointment as explorer-in-residence at the National Geographic Society, Davis was assigned a lofty task – to change the way in which the world values culture. He resolved to carry out this mission through the art of storytelling and, at the Koerner Lecture, he proved that inspiring the imaginations of others by bringing words to life is a sure means of achieving this goal.

At the outset of his talk, Davis proposed that the sphere in which one is born “is just one version of reality.” According to him, all of humanity is genealogically related. As a result of his personal experience of travelling around the world, immersing himself into a plethora of cultures, he believes that our brothers and sisters around the globe can offer us new approaches to perceiving the world and “orienting ourselves in ecological space.” He then took the audience on a world-wide journey transcending space and time and imparted the valuable lessons he has learned.

Early in his talk, he brought the audience to Polynesia, speaking of the voyage of a sacred canoe, the Hōkūle‘a, named after a sacred star of Hawaii. On this voyage, there was a wayfinder who was in charge of leading the journey, relying solely on all of his human senses to do so. The wayfinder would sit on the vessel and absorb every detail along the entire trip, from weather patterns to wildlife, to ensure a definite sense of direction.

Next, he spoke of the Amazon, “a forest the size of the face of the full moon,” where the indigenous peoples were deeply in tune with the land on which they lived. He noted that since the Amazonians viewed the heavens and the forest as equal beings, they could not distinguish the colours blue and green. In fact, for the Amazonians, “the route to godhood was taken by plants.” They perceived botanical organisms as being enabled to a “different way of knowing.” Similarly, Davis continued, the Inca peoples in the Andes also held a strong reverence for nature, viewing the mountains as omniscient deities and predictors of one’s destiny.

Later, he told the tale of the peoples of sub-Saharan Africa, whose culture not only embodied revering a god, but becoming it. The name of their religion, voodoo, means “spirit of god,” Davis said. As such, he explained, voodooists lived on a metaphysical plain, possessing their god’s spirit and invoking their god’s appeals.

During his lecture, Davis also mused on the concept of language, likening a language to a “watershed of thought,” an “ecosystem of possibilities.” He remarked that no phrase for “thank you” existed in the language spoken in the forest of the Penan tribe in Borneo. He noted there was no need for such an expression there because all things large and small were shared. Where the Penan peoples valued belongings, he reflected, the peoples in the outback of Australia placed importance upon the rejection of progression. Living life on a continuum, the words “past,” “present,” “future” and “time” were absent from their cultural vernacular.

Towards the end of his talk, Davis reiterated the significance of culture and the unparalleled lessons it offers us in our day-to-day lives. Further, he associated a loss of culture with a forfeit of economic development and prosperity. His sage words left the audience to contemplate culture as a source of wealth and richness, an inspirer of dreams and a motivator for optimism in the face of daily struggles.

By Kate Tschirhart, communications coordinator, Faculty of Environmental Studies. Photographs by Daniel Lapadula.