The 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28) wrapped up on Dec. 12, with more than 50,000 delegates who descended upon Dubai in the United Arab Emirates for the annual international climate summit.

Among the delegates was York University’s Angele Alook, an assistant professor in the School of Gender, Sexuality & Women’s Studies, and her research team: community-based researcher Lydia Johnson, of the Lac La Ronge Indian Band, with the Centre for Indigenous Knowledges & Languages; and PhD student and graduate associate Ana Cardoso.

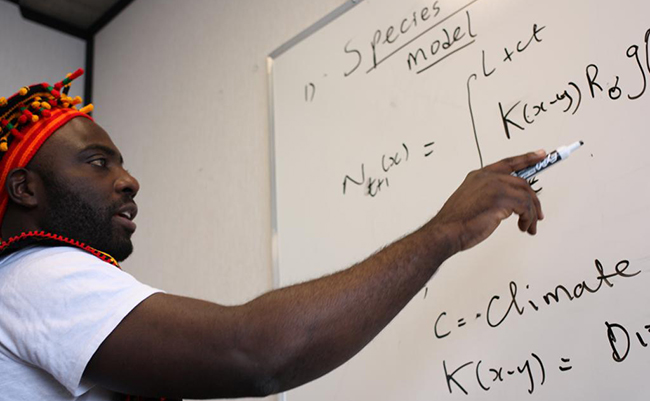

The trio were there to conduct field work for a project called Indigenous Climate Leadership and Self-determined Futures, which aims to highlight and advance the understanding of Indigenous methods to mitigate climate change, derived from traditional knowledge and governance, among Indigenous activists and leaders, knowledge holders, other researchers and policymakers.

The project’s findings will eventually be shared through both academic publications as well as several arts-based approaches, including photography, video and graphic novels. It is funded by the Catalyzing Interdisciplinary Research Clusters initiative, created by the Office of the Vice-President Research & Innovation at York University.

Alook, who is a member of the Bigstone Cree Nation in Alberta, talks about the Indigenous-led project and her COP28 experience in this Q-and-A below.

Q: What was your main objective with attending COP28?

A: My team and I went to Dubai to interview several Indigenous leaders from Turtle Island (North America) and elsewhere in the world. We wanted to talk to them on the ground as they are simultaneously actively engaged in climate discussions with world leaders, government agencies, scientists and organizations. We believe capturing their stories in this moment will provide us with their best insights for our project.

Much of our questions focus on learning about what motivated them to attend COP28, the challenges they face in a colonial space, their experience in policy talks and negotiations, and their climate actions back home.

We also presented on several panels at the Indigenous People’s Pavilion and Canada Pavilion. We participated in the Local Communities and Indigenous People’s Platform youth knowledge holders discussions. We also participated alongside our Indigenous kin in several United Nations-sanctioned actions to promote Indigenous rights and human rights.

Q: Why is Indigenous participation at events like COP28 important?

A: COP28 represents the biggest international stage for climate change talks, but Indigenous Peoples make up only a small number of attendees. Indigenous Peoples are knowledge keepers and I believe they have real solutions to deal with climate change. We have a relationship to the Earth grounded in land-based practices and sustainability, so Indigenous Peoples’ voices are incredibly valuable if we want to see effective climate policies developed around the world.

There’s also a lot of advocacy work that happens at these conferences to uphold Indigenous sovereignty, including in international treaties. Certain parts of the Paris Agreement, like article six, which focuses on carbon markets, could have serious implications for Indigenous Peoples and their assertion of rights. Some Indigenous communities have voiced their concerns that article six could lead to their lands or territories being exploited by companies or governments for carbon offsetting. It’s important Indigenous Peoples are fully consulted on these issues, as they often are the ones most impacted by these decisions.

Q: COP28 marks the fourth time you’ve attended the summit. What progress do you see being made for Indigenous Peoples in climate discussions? What was your overall experience like?

A: On progress, I think Indigenous people involved in negotiations at COP27 would point to the creation of the climate Loss and Damage Fund, which could benefit smaller nation states with Indigenous communities most affected by climate change. This year, they also announced a Gender-Responsive Just Transitions & Climate Actions Partnership with former United States secretary of state Hillary Clinton in attendance. However, these funds go to nation states that colonize Indigenous Peoples, who are demanding direct access to these funds, instead of those who continue to colonize us.

I do think it’s one thing to come to COP as a business person or civil servant, but I think it’s a very different thing to come as an Indigenous person. There’s a whole other world taking place here among Indigenous attendees in terms of relationship building. There is an immense amount of Indigenous knowledge from around the world being shared with one another. I think it strengthens our sovereignty and our own Indigeneity to tell these stories to each other and acknowledge our shared experiences.

Personally, the most hopeful thing I’ve felt at COP28 seems to be this growing solidarity among Indigenous Peoples. More and more Indigenous people are showing up as bold leaders in these spaces, sharing their knowledge and using their voices. It’s been an amazing experience for me and my research assistants to connect and listen to them.