A popular colloquialism is that one “can’t see the forest for the trees.” And yet can we even see a tree for what it is?

“The tree which moves some to tears of joy is in the eyes of others only a green thing that stands in the way,” wrote William Blake in 1799. “Some see nature all ridicule and deformity… and some scarce see nature at all. But to the eyes of the man of imagination, nature is imagination itself.” During the origins of the capitalist era, Blake opposed imagination to the Enlightenment project where a deformed nature was to be demystified and corrected. No more deep dark woods of the Grimm fairy tales, in this utilitarian world that we have inherited the trees are meant for harvesting. Forests have been uniformly managed into columns of statistics.

In “What We Lose in Metrics,” an exhibition by Public Studio (York alumna Elle Flanders and Tamira Sawatzky) at the Art Gallery of York University (AGYU), visitors were asked to consider what is lost in such metrics; those statistics that come from turning forests into standing reserves for commodity exploitation. What has been given up and what needs to be regenerated in this pragmatic notion of the natural world in which we all participate?

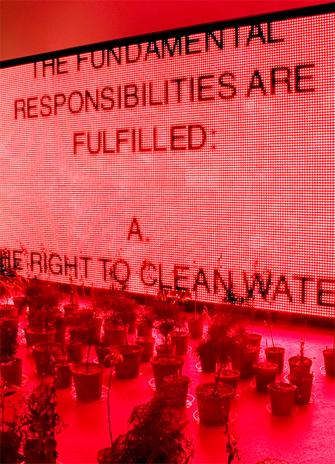

Curated by Emelie Chhangur, AGYU assistant director/curator and Philip Monk, AGYU director/curator, “What We Lose in Metrics” was on display at AGYU from April 13 to June 16. As part of the exhibition, the work Everything is One featured a collection of living saplings nourished by a 20 by 10 foot LED screen that was transformed into a grow lamp. The screen displayed text from the Rights of Nature, a written work created for the exhibition by Haida lawyer Terri-Lynn Williams Davidson.

When the show closed, there was a plan in place for the saplings. Each of the tiny trees was moved to a space outside the gallery to “harden off” and become accustomed to the natural environment. On July 4, during a special event, the saplings were replanted as part of a special Bioplan forest on York University’s Keele campus, where it is hoped they will thrive and live in perpetuity.

“The saplings were chosen by Public Studio in consultation with world-recognized Ottawa-based author and scientist Diana Beresford-Kroeger, whose life-work has been dedicated to the development of an ambitious Bioplan for the future of the world’s forests,” said Chhangur. “Over the course of the exhibition, the forest has thrived and now that the show has closed, the AGYU and Public Studio, in partnership with York University’s Grounds Department in Campus Services & Business Operations, planted the trees beside Stong Pond, ensuring that Beresford-Kroeger’s Bioplan – and Public Studio’s work – will remain a permanent part of the University’s landscape and future ecology.”

Tim Haagsma, manager of grounds, said the exhibition and the planting was one of the most interesting experiences of his career.“This was such an interesting exhibition and the neatest experiment,” said Tim Haagsma, manager of grounds for Campus Services and Business Operations and the operations staff member who assisted with the replanting effort.

“The trees survived indoors during the exhibit, there were about 120 saplings including a variety deciduous and conifer trees, all native to the area,” said Haagsma. “We moved them outside to harden off and become used to the environment and then planted them on the Keele campus site. It was four hours of hard work and we are watering them diligently because it is so dry.

“It was an amazing experience, one of the best I’ve had because it brought 20 people together, including academics, artists and operations staff, to work for the common good of the University,” said Haagsma.

Pine, hemlock, different varieties of oak, basswood and birch were some of the many types of trees planted by the pond. They are being cared for by operations staff to ensure they grow and flourish in their new environment.

Artists Flanders and Sawatzky, who conceived and created the works of art in the exhibition, offered the following message about their experience: “The AGYU gave us an opportunity as artists to work across disciplines, to break down the walls of the gallery metaphorically and literally to think about the fragility of our world and our place in it. Our show was a meditation on the forest and the space it has occupied since post-enlightenment thinking. We began to ask: Are we truly enlightened? What other kinds of knowledge have we forgotten in our race to metricize and order our world? In order to connect these seemingly disparate ways of knowing, we felt the exhibition could put into action the bioplan of diverse tree planting by acclaimed botanist and biochemist Diana Beresford Kroger’s Bioplan. Addressing the rapid degradation of nature and our distance from it, Beresford Kroeger has suggested there are 10 trees that can save the world. In a small symbolic gesture, we have decided to grow these trees in the gallery and then plant them on the York University campus so that we can all learn together. One of the lenses through which we looked at the forest was the juxtaposition of the worlds of video games and cinema in order to look at the ways in which culture reflected the forest in both old and new cinematic languages.”

In addition to being at the AGYU, “What We Lose in Metrics” was also primary exhibition of the 2016 Scotiabank Contact Photography Festival.

Public Studio received support from the Ontario Arts Council for the development and production of this project. See more about their work at www.publicstudio.ca.