On Sept. 30, York’s Canadian Writers in Person course and lecture series presented poet Ian Williams reading from his poetry collection Personals. Special correspondent Chris Cornish (BA Hons. ’04, MA ’09) sent the following report to YFile.

The friends I friended do not show.

One by one, yellow leaves, they text

– the snow, the snow, the snow, the snow –

sad emoticons of their faces.

from Personals

by Ian Williams

Ian Williams admits going on a diet from technology from time to time. He quit Facebook for four years but recently returned to find some interesting revelations. “In many ways, these technologies keep you humble, the way learning another language keeps you humble,” he said during his presentation Sept. 30. “No matter how old you are, you still want people to like you, to notice you, to appreciate you, but we’re never quite satisfied.”

Williams said we long for intimacy and connection, and technology seemingly makes this easier, yet we are perpetually disappointed. His recent poetry collection Personals is composed of “almost love poems” in which its speakers almost have satisfying connections but ultimately face disappointment. Williams himself did not disappoint and made a strong connection with his Canadian Writers in Person audience.

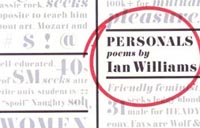

The title and the book’s cover design is a riff on the motif of personal ads, in particular the “missed connections” where strangers try to build love from momentary glances or stray comments. The poems in the collection are frequently paired to face each other across the page, sometimes with something in common, but “not quite successful in finding their mate,” he said.

Williams’ words playfully (and painfully) consider what it means to be people in a world where we share our lives publicly through social media yet struggle with true intimacy.

The signature set of poems in the collection, titled “Rings,” expresses the indeterminacy of desire, the circular patterns of problems in relationships with their should-haves and would-haves. The form of each poem from this section reflects an almost completion, being just one line short of the required fourteen to be a sonnet. They end in an actual ring, the text twisting in an endless loop, open to multiple meanings. In the concluding poem of the section, “Nutrition Facts,” Williams nonetheless offers the “only instance of pure genuine day-to-day quotidian love, pure sweetness,” the reader’s reward for the purgatory of its previous pieces.

In another poem called “Condition,” set during what Williams imagines to be a bad date, two would-be lovers repeatedly exchange empty platitudes of “How you doin’?” and “Fine thank you and you?” in tune to the poet’s Pavlovian cues. This was one of the evening’s finest unscripted moments, where Williams enlisted student volunteers to read the two different voices of the poem. With the limitation of one microphone, the poet put his arms around his two readers and drew them close so they could all be heard. In this odd but lovely moment, Williams embodied one of the themes of his collection, strangers connecting intimately on a public stage.

This performance element also seemed to reinforce Williams’ belief that we are constantly “performing ourselves,” our identities shifting according to changing circumstances. This led to some discussion about the different voices in poetry, how they are often textual constructions that borrow from social constructions. Finding one’s voice in this polyphony, both as a reader and a writer, sometimes requires patience and a little bit of natural maturity. Williams equates it to his experience of playing classical music, noting that he didn’t appreciate Schubert until he was a bit older, the composer’s complexities unlocked as he became more quiet and still.

This performance element also seemed to reinforce Williams’ belief that we are constantly “performing ourselves,” our identities shifting according to changing circumstances. This led to some discussion about the different voices in poetry, how they are often textual constructions that borrow from social constructions. Finding one’s voice in this polyphony, both as a reader and a writer, sometimes requires patience and a little bit of natural maturity. Williams equates it to his experience of playing classical music, noting that he didn’t appreciate Schubert until he was a bit older, the composer’s complexities unlocked as he became more quiet and still.

Williams’ poetry, though it plays with traditional forms and meters, is a response to the present. Evolving technology influences language, in which friend (and unfriend) are now powerful verbs, opening up fresh territory where writers can test poetry with contemporary issues. In “Dip,” he uses the language of texting to reflect on the feeling of a declined party invitation, distanced by the cheerful but ultimately lonely emoticon. “One of the saddest things in the world is the party dip that was never touched. Your guacamole confronts you.”

Though he’s also an academic, Williams’ poetry is not dogmatic and in person he’s “pretty chill.” Just as he’s open to the variability of life, his work is open to varying interpretations. Like the strangers in his poems, there is a space where poet and reader can almost come to know each other, and almost have an intimate conversation:

I make it difficult, true,

but possible, clearing only

what you need to get in:

two tire paths in the heart’s

snowy driveway.

The Canadian Writers in Person series of public readings at York University, which are free and open to the public, are also part of an introductory course on Canadian literature. It is sponsored in part by the Canada Council for the Arts. For a full schedule of upcoming writers this year, see the Sept. 15 issue of YFile.